http://www.writingandwellness.com/2016/09/13/writing-to-find-the-hero-in-ourselves/

Writing to Find the Hero In Ourselves

by Carol Pratt Bradley

My family enjoys watching historical films and we loved the 2003 movie, Luther, about Martin Luther and the Reformation.

My family enjoys watching historical films and we loved the 2003 movie, Luther, about Martin Luther and the Reformation.

I had also read a book about William Tyndale, the man who translated the Bible into English. At the time, I was searching for an idea for my thesis novel for an MFA program, and this time period piqued my interest.

In my research I ran across the name Anne Askew, an English noblewoman, reportedly beautiful, literate, and devoted to the Bible. While in prison for heresy, she’d penned her own book, titled The Examinations of Anne Askew.

I located it in the library on campus. It was even available for sale on Amazon. Five hundred years after her death, this woman was not forgotten in history. When I read her story, I knew I wanted to write a book about her life.

What was it about people like her, and Luther and Tyndale that made them so memorable, even centuries after they died?

People look for heroes, male and female. We need them. Here was a woman I could write about, and in the process, explore what it is to be one.

Searching for My True Heroine

The biggest challenge that I faced in writing the novel was trying to find the real Anne.

I read her book and also two poems attributed to her, and studied the few known details of her life. Who was she? What was her temperament? In her book, she comes across as a fiery zealot with a biting wit, who did not hesitate to belittle her adversaries. But was that zealot the real woman? Or were her words altered by her editors for their own purposes?

The Protestant John Bale, who smuggled her written account out of England, published it in Europe, and distributed it throughout England a year later. Bale, nicknamed “Bilious Bale,” reportedly had a gloomy, quarrelsome disposition.

John Foxe also wrote an account of her in his book The Acts and Monuments, better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Both men likely put their own editorial stamp on her words for their own religious and political purposes.

I finally concluded that I couldn’t know exactly what she was like. She may have been a real person, but I was writing a book of fiction. So I wrote her the way I felt her to be.

To me she would have been a compassionate, brave woman who did her best in her circumstances, trying to live according to the morals she found in her beloved Bible. Like all humans, she made mistakes, she was loved and hated, she was kind but sometimes impatient.

Above all, she was a person who felt deeply, who lived true to herself.

After the Research is Finished, Where Do You Start the Book?

After researching the time period, reading Anne’s account of her trials, finding out about her circumstances, I was uncertain where to start the book.

One morning I woke with a picture in my mind, in vivid detail: fifteen year old Anne on the night of her forced marriage to the stranger who had been betrothed to her sister, now dead of the fever. Her books were hidden beneath the bed: her Tyndale New Testament, a Bible in English, and her journal.

She’d woken in the night, alone, frightened and lost. While her new husband slept, she knelt on the floor and removed the books from their hiding place, holding them close to her chest, breathing in the familiar smell of them, a reminder of her childhood and freedom. She took out the journal, and in the darkness, spelled out her name, over and over: I am Anne. Anne Ayscough.

This scene capsulated the heart of the story for me: Anne’s fight to preserve her own identity and beliefs in a hostile atmosphere that demeaned her worth. I wrote that scene first. It became the prologue, and after many revisions is now imbedded within the novel.

But it remains the pivotal moment for me, when I felt that I connected with Anne.

What My Book Taught Me: There Are Truths Worth Living For

Writing Anne’s story disturbed me, saddened me, angered and confused me.

How could such injustices happen? What kind of twisted politics would seek to compel individuals to believe a proscribed way, threatening death if they dared to think differently? Not just death, but as horrible a one as they could concoct, like burning someone to death.

Why do people seek to dominate over others? In politics, in communities, in families?

The world’s history seems a complicated mess. But in every century, there are people who live true to their own conscience despite the opposition they face, despite the consequences. No matter their end, they triumphed.

I learned that there is something sovereign within men and women that resists coercion, fighting for the right to choose even if it is denied. I learned that there are truths worth living for, even dying for. No matter what period of time in earth’s history, it is the same.

Would I Be as Brave as My Heroine?

I think another reason it upset me is it made me look in the mirror.

How different would Anne’s life have been if she had lived in a different time period? I wondered. How different would my life be if I had lived in 16th century England?

I take for granted the freedom to believe as I choose. She did not have that. And yet she deliberately decided not to be silent, to speak out no matter the consequences.

What would I do in her circumstances?

I haven’t looked inside myself deep enough yet to know the answer to that.

Another thing that disturbed me: do we learn from the past? Or are we just repeating the mess over and over?

To Write with Power and Wisdom, I Must Search Deep Inside Myself

Is writing a spiritual practice for me? Yes.

There are many terms associated with the word spiritual: sacred, inner dimension, bliss, search for meaning, supernatural, the soul, sense of self, to name a few. For me, spirituality is searching for something larger and wiser and better than myself, to be able to comprehend with more than my own limited ability.

I want to combine the physical and spiritual to enable me to reach higher, dig deeper in my search for understanding.

To write with power and wisdom, I must search deep inside myself, reaching for a place not seen but only felt.

How My Research Put Me In Touch with the Past

The physical—what we can see, hear, smell, taste—seems intricately tied to the spiritual, the things we cannot touch or see, that are just as real.

I think this is why I like to write about the past, time already gone, disappeared around the circle of history.

I traveled to England to find Anne Askew. The Guildhall in London where she was put on trial is no longer standing, but the building in its place was built from some of the same stones. I touched a stone, my hand connecting physically with something from Anne’s time, and felt closer to her.

At Sudley Castle, I walked the gardens around the chapel where Anne’s friend Queen Catherine Parr was buried, and felt that somehow that I walked, not into, but alongside, the past. It was a reverent feeling.

The passing of time changes the physical: buildings crumble into decay, disappear, landscapes change. But somehow everything that happened before remains, hovering in the air around us, still beating and breathing. Nothing is gone.

We cannot see it with our eyes, but it is all still very real to us through the spiritual, or senses unseen.

Taking the Picture in My Imagination and Molding it Into a Story

I have several projects started, and my problem is which one to pursue to completion.

A story I wrote several years ago keeps coming alive in my mind. It’s a departure from my previous novels: a historical fantasy set in medieval times in a little town that I visited in England—Castle Combe—a town still the same after more than five hundred years. The charming attached houses built by the cloth weavers line the curved streets, the same marketplace, and the fourteenth-century church, the wood that edges the town. I close my eyes and I still see it, still feeling that as I walked its streets I stepped alongside the past.

I studied the history of the place, incorporating people into my story that had been associated with the town, like Sir John Falstaff, made famous in Shakespeare’s plays. I also used the ancient, crumbled castle that stood on top of the hill overlooking the town. The ancient legends about the haunted Wood fascinate me—the ghosts of the Saxons and Danes still locked in combat.

I also used some of the vivid poetic images from John’s Book of Revelations in the New Testament, like vials and open doors that never shut. After I’d written a draft of the story I read Shakespeare’s Sonnet 64. It deals with similar themes: time bringing decay upon the physical things of earth, and taking away those we love.

I hope I can mold this story to fit the picture in my imagination and be able to share it with my readers.

(Read more about Carol on her previous Writing and Wellness post.)

* * *

Carol Pratt Bradley is an historical novelist with a Master of Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing from Brigham Young University.

Carol Pratt Bradley is an historical novelist with a Master of Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing from Brigham Young University.

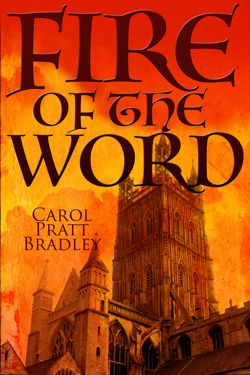

Fire of the Word was originally written as her master’s thesis. Her first published novel, Light of the Candle, was published by WiDo in January 2015. The sequel to Light of the Candle will be released soon.

Carol lives in Mapleton, Utah with her husband, Bryan, near their four grown children.

For more information on Carol and her writing, please see her website, or follow her on Pinterest or Twitter.

Fire of the Word: Young English noblewoman, Anne Ayscough, lived during the turbulent times of Henry VIII, when Protestant reformist ideas clashed violently against entrenched Catholicism.

Fire of the Word: Young English noblewoman, Anne Ayscough, lived during the turbulent times of Henry VIII, when Protestant reformist ideas clashed violently against entrenched Catholicism.

Yet many, especially the wealthy, owned William Tyndale’s New Testament, including the household of Sir William Ayscough in Lincolnshire. In her family home, Anne grew in an atmosphere of openness, gleaning new ideas from her brothers who were educated at Cambridge, a hotbed of Protestant ideals.

At the age of fifteen, Anne’s life changed drastically. Her older sister Martha, betrothed to a son of a family staunch in the Catholic faith, contracted a fever and died. With the financial arrangements for the marriage already in place, Anne’s father ordered her to stand for her dead sister, forcing his daughter to enter a loveless marriage.

England’s religious war became Anne’s as she clung tight to her own ideals in her husband’s house. This eventually brought her into the center of the vicious political and religious battles where she was faced with a choice.

Anne could deny the truths she had embraced as a young woman and live, or hold fast to her beliefs and be put to death.

Available at WiDo Publishing.